A landmark judgment

Turns out that knowing there are two sexes doesn’t make you a fascist

Part 1

I’m starting to write this on Wednesday 6th July, just a couple of hours before Maya Forstater receives the judgment in her employment-tribunal case. Unusually for a first-instance hearing, she was given notice yesterday that the result is coming today, probably around 11am—normally the judgment just lands in your inbox, or your solicitor’s. It’s now just after 9am, and since I’m likely to be busy later—I’ve offered to be phone-wrangler and bag-carrier if she is asked to do media appearances—I thought I’d start writing before it all potentially goes crazy. (Ongoing political chaos means we’re totally uncertain whether any outlets will be interested in the judgment, but there are plenty of people who have been following the case to whom it will matter even if the government falls today.)

This has been a three-year odyssey for Maya. Since she filed her claim in the first half of 2019 she has received an outrageously flawed judgment in the employment tribunal, when it was decided that her straightforward, ordinary understanding that humans come in two immutable sexes, and that sometimes that matters for people’s rights, was on a par with Nazism: a belief too harmful to society at large for its adherents to be protected from victimisation at work or in the provision of services. I now know Maya well enough to have some inkling of how much that hurt. Her stance was measured against the so-called “Grainger criteria” used to decide whether a belief is covered, and was judged to fail the fifth by being, in the legal jargon, “not worthy of respect in a democratic society”.

Of course she knew that was ridiculous—her beliefs accord pretty much completely with UK law, and last time I looked it’s a democratic society (yes, I know, not looking like a shining example right now). But the judgment declared open season on women who stand up for sex-based rights for the haters and bigots who want us silenced, shunned, sacked and generally drummed out of public life. Maya’s a remarkably strong person, but to be brought to the 21st-century version of the pillory, and by a judge no less—declared a legitimate target for anyone who wanted to liken her to a Nazi—has obviously been a horrific experience. I’ve experienced something similar on occasion, and I’m now close enough to her to have some inkling of what she has been put through—but also to know that no one else can fully appreciate the depths of anger, despair and shame it has inflicted on her.

I was one of the many, many people who donated to Maya’s original crowdfunder back in 2019, and that meant I got the email that went out to her supporters saying that she had lost her first hearing. It was shortly before Christmas, and I was walking through pouring rain to a party for Standpoint magazine. Now sadly defunct, at the time it was one of the few outlets willing to publish what I wrote about trans issues.

I had just come from a row with someone who was overseeing a film about transwomen in sport. At the very last minute, he had intervened to remove the words “male” and “female” from the final edit, in favour of “trans woman” and “natal woman”. It was a horrible conversation with someone I had respected, and although in the end I managed to get him to put things back the way they were before, it had left me deeply shaken. If someone as clever and reasonable as him could not see how essential it is for women’s rights not to lose these fundamental words, what hope was there?

And then Maya’s email landed, saying, in effect, that the argument I had just had marked me as “not worthy of respect in a democratic society”. I can’t remember whether Jane Clare Jones rang me as I walked along the Mall, or whether I rang her, but I remember we both cried. I had never personally been given reason to believe my job was at risk, but this judgment meant that if anyone wanted to complain about me, either internally or externally, I too would be fair game. I know, because I and Maya have both heard it many times since, that many other people had the same feeling of despair, realising that what they had already said in their workplace had put a target on their backs, or else that they would now have to remain silent about any incursion into women’s spaces for fear of becoming unemployable.

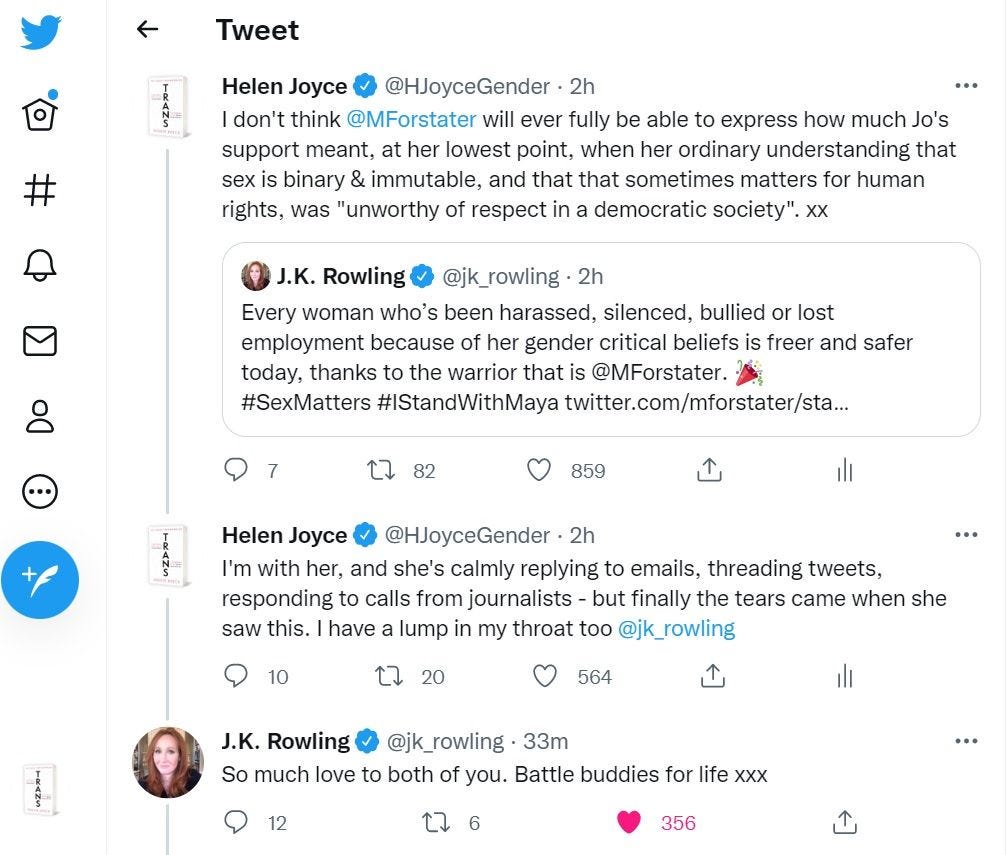

And then J.K. Rowling tweeted. “Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep with any consenting adult who’ll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real? #IStandWithMaya #ThisIsNotADrill”.

It utterly changed the mood. Suddenly, instead of being a former expert on tax flows and development who had said something so horrific at work that she had rightly been made unemployable, Maya was a global cause célèbre. It gave her courage to fight on—and gave courage, too, to all the gender-critical women who had just been shown just how precarious our situation was, and how arbitrary state power can be. Fear turned to outrage, and then to determination. Maya’s crowdfunder for her appeal went gangbusters.

In the Employment Appeal Tribunal, the judge overturned the original decision in its entirety. I often think how lucky it was that the first ruling was so awful. If it hadn’t been, Maya’s case would not have gone to appeal—and the decision that her belief in binary sex was indeed “worthy of respect in a democratic society” would never have set a precedent that now protects us all.

The latest hearing, in March, was back in the lower tribunal, and was to establish whether she was, as a matter of fact, victimised because of her beliefs. She’s been on tenterhooks waiting for this decision for weeks now. Maya had estimated that it would come by the end of May; it’s been more than a month longer than that already. I work closely with her, and I see how productive and effective she is—as another colleague said yesterday when we decided that a new project would have to wait until some other ones were closed off, “after all, there are only three of Maya.” But she is distracted and fearful. If after all this it’s decided that the details of her employment status mean that CGD does not have to answer for victimising her—or if it’s decided, as CGD’s lawyers argued, that she is entitled to hold the bizarre and bigoted belief that sex is real and binary but not to say so at work—she will understandably feel that a deep injustice has been done.

And she’ll have to decide whether to appeal, when she is heartily sick of this nonsense, and also has far better things to be doing. Sex Matters, the human-rights organisation she and others founded, and which I took leave of absence from The Economist at the beginning of April to work for, is performing miracles on a shoestring. But there are only so many hours in the day—and only three Mayas and a handful of part-timers—to fight the endless fires, start the next campaign, follow through on the previous ones, get the word out, and so on and on.

I’ll write more later, when I know the outcome. It’s 10am now…

Part 2: Thursday morning

As readers will know by now, the judgment was in Maya’s favour. She and I spent the day in the offices of a Westminster think-tank which kindly let us squat in the kitchen and use the wifi. We had prewritten two press releases, one for good news and one for bad. I felt like I was drowning a kitten writing the “bad” one and making Maya read it.

Once the “bad” one had been deleted and the lawyers had declared themselves satisfied with the final tweaks to the “good” one, and it had gone out to the press list, things were actually pretty calm. Political chaos obviously dominated the news cycle, but newspapers still have column inches to fill and not all journalists are political correspondents. I vividly remember during the financial crisis in 2008, when I was education correspondent working on the Britain section of The Economist, writing a long piece about the future of British universities, even as HSBC looked likely to collapse. It was a strange feeling, but it taught me that when you have a specific beat you shouldn’t worry when the news cycle is elsewhere. Just do your own job and let the politicos, or the financial or war correspondents, or whoever, do theirs.

And in fact we did get excellent coverage, despite the craziness. Most papers and websites wrote up Maya’s story from the press release; during the day some broadcast media called and arranged interviews for the following morning. Maya made it onto Thursday’s Today programme on Radio 4 as the only non-political story, and providentially went on air about ten minutes before Boris Johnson finally said he would step down from the Tory Party leadership. (You can listen back if you’re signed up to the BBC; she’s on at around 8.40am.) There will be more interviews and op-eds over the coming days and weeks, I’m sure.

Late afternoon we met up with Anya Palmer, the wonderful barrister who persuaded and supported Maya to take the case in the first place. Champagne was had, and then an evening in the pub was spent with whoever was around, and could tear themselves away from the scrolling political news.

I can’t share many pictures, because I’m not sure who’s “out” as gender-critical—and isn’t that a telling indication that there’s still a long way to go before we can really feel safe in expressing our understanding of the embodied nature of human existence. But I’ve added a few at the bottom of this article, and may add more if and when I get permission.

What will be really interesting to watch from this point on will be how the “narrative” changes. There won’t be a definitive moment when outlets or individual journalists stop thinking of Maya as a bigot, recognise that she was motivated by a sense of justice, and understand that she suffered workplace victimisation. It’ll happen slowly. But I’m sure it will happen, bit by bit. Just as most people will now tell you they opposed the invasion of Iraq, even though opinion polls at the time showed solid support for it, the very same people who thought three years ago that Maya must have done something terrible, and must have deserved everything that happened to her, will eventually regard her as having led a campaign for women’s rights. None of them will ever acknowledge that their position has changed.

After the first judgment lazy journalists recycled and embellished transactivist talking points, assuming that she had “misgendered a colleague” (in fact she had no trans colleagues, and had not misgendered anyone); that she was seeking the right to harass trans people (she never harassed anyone; whether an action constitutes harassment is highly context-specific; and nothing in any of her judgments had any bearing on that). I think they assumed that nobody could really have lost their job for simply saying that sex is real, and that the law on gender recognition should stay as it was, so Maya must have done something much worse than that.

After the second judgment, that shifted a bit. Now Maya’s beliefs were at least recognised not to be on a par with Nazism, but they were talked about as if they only just cleared that low bar. She was still a bigot, but one whom, perhaps regrettably, others were required by law to accommodate to some degree.

And when she came back to the employment tribunal in March for the hearing on the facts, CGD’s barristers, and the employees called to give evidence, argued that her beliefs had never in fact been the problem—as they had to, because those beliefs were now recognised as protected. Rather, the problem was the unacceptable way she phrased them; the fact that she sought to impose them on others; the way their expression infringed on other people’s rights. The latest judgment neatly demolished all that nonsense. Everything Maya said, did and tweeted on the subject of gender-recognition reform, and sex-based rights more generally, was recognised as being simply a statement of her protected beliefs.

The next stage in Maya’s rehabilitation will be the realisation that, far from being the aggressor in her workplace, she was a victim of discrimination. She was working at the recently set up European branch of an American think-tank headquartered in Washington, and her colleagues in head office had adopted the latest American social-justice doctrines about race and gender. They clearly regarded themselves as entitled to be outright bigoted towards anyone who doesn’t share their beliefs. Fortunately for workers in the UK, we’re protected against bosses and colleagues who think they have the right to impose their own beliefs on others. Just as a Christian boss can’t sack an atheist for being an atheist (or indeed vice versa), no UK employer can force an employee to believe or say that men can become women. And because of Maya’s quiet heroism over the past three years, we can all feel a bit safer.

And two more pics that I got permission to share after I had sent the newsletter

And finally, my favourite picture of the evening. I have just casually admitted that I do not care at all about fonts—not even Comic Sans. If I can read it, that’s good enough for me. My sister, beside me, has just agreed, including the bit about Comic Sans.

Facing us are Sex Matters’ document manager, who does all our layout, copyediting and proof-reading, and an increasing amount of the writing, and to her right as you look at us, our designer and UX specialist. Neither of them could believe what they were hearing, and I’m not sure they’ll ever forgive us.