Standing for Women: the fallout

How accusations of bigotry, like cooties, are contagious

First an addendum to last week’s issue. After reading it, Julie Bindel dropped me a note to tell me something I hadn’t known: she was the first journalist to expose the child-grooming scandals, and had been trying to get stories into papers for ages before the Sunday Times finally took one (among the papers too worried about being labelled Islamaphobic was the Guardian, by the way). It was after her piece that Andrew Norfolk picked up the story and did a great deal of excellent reporting. Julie tells me she is working on a podcast about it all, which is sure to be excellent. I’ll share once it’s released.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

So it seems I’m going to write more about the fallout from the Standing for Women event in Brighton two weeks ago. I’d love to write about something else, but the commentary and arguments continue, and they’re taking up all my available headspace, and then some. To be fair, I’ve learned a lot from them. The experience has clarified my thinking, and helped me to understand that of other people better.

Here’s a selection of interesting responses from other people, some standalone articles and some Twitter threads (and a piece of spoken-word poetry).

Feminism’s dangerous new allies, by Julie Bindel (not strictly speaking a commentary on recent events, since it’s from 2020. But it reads like it could have been written yesterday.)

Feminists must reject left and fight, by Louise Perry (another fascinating article from 2020, and if I’d read it then I’d have known Julie broke the grooming scandal. Of everything I’ve read in the past two weeks, it comes closest to my views.)

Feminism and the Far Right: Let Women Speak, by Harvey Jeni (which attracted glowing praise from several prominent leftwing women, including Julie Bindel and Beatrix Campbell).

Feminism, by Gia Milanova.

A thread by women’s sector campaigner Karen Ingala Smith, in which she explains that her socialist feminism cannot be subordinated to the goal of defeating transgender ideology.

A thread by writer Claire Heuchan on the distinctions between radical feminism and gender-critical viewpoints, and what she, as a radical feminist, sees as the fundamental problem with single-issue GC campaigning.

A thread by feminist writer Raquel Rosario Sánchez on how much she dislikes white women stepping in to talk over women of colour on the subject of racism.

Feminism and the Far Left, by DJ Lippy, aka MakeMoreNoise, a frequent attendee at Standing For Women events.

And finally, a video by Aja, another frequent attendee and one of the stewards in Brighton, on what she sees as a class divide within feminism that drives much of the discord.

So you can see how much this subject has taken up of my and other people’s time! And this is only a small selection of what I’ve read. I doubt I’ll finish saying everything I want to say today, and may return to the subject once the dust has settled.

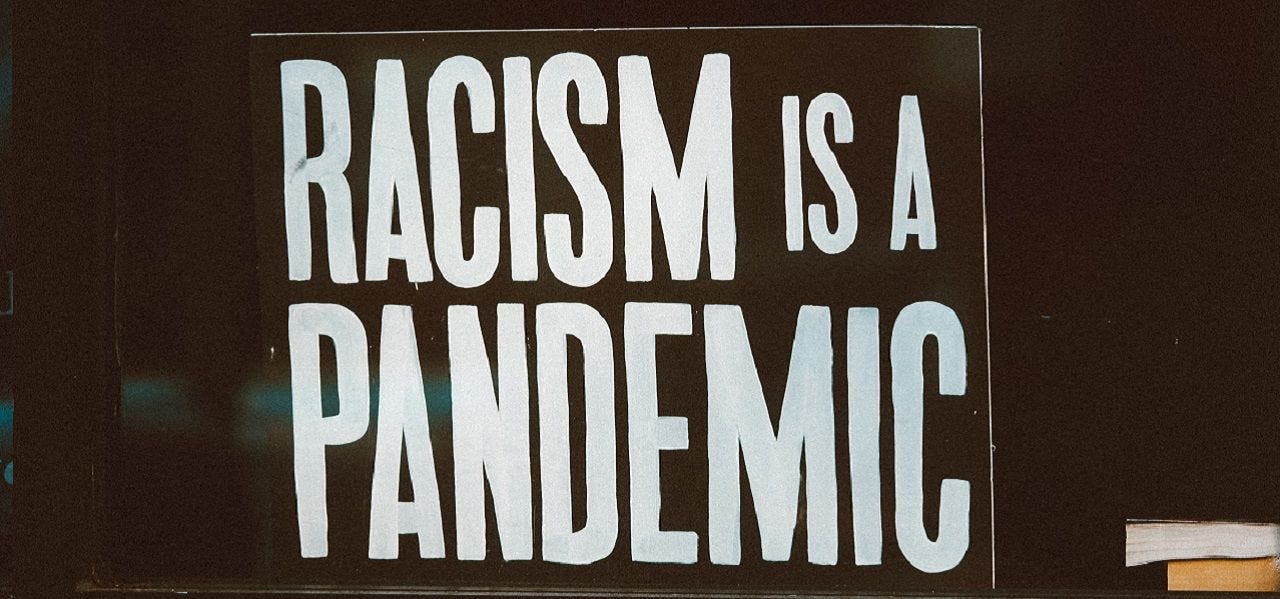

My first observation is that, of all the types of prejudice and bigotry, racism is the one it’s most dangerous to be accused of. It is of course a virulent and widespread form of bigotry—but then, so is misogyny, and that doesn’t seem to have anything like the same toxicity. The thought has crossed my mind that that’s because racism, unlike misogyny, hurts men, too—and maybe that’s a part of it. But I think more important is America’s particular neuralgia on the subject. I remember noticing, early in Donald Trump’s presidency, that it was the accusations of racism against him that had most force, even though at the time he was facing what seemed like pretty credible accusations of rape.

Dubious claims of racism are therefore a very powerful, and tempting, weapon. One such instance returned to the headlines this week: the cancellation of author Kate Clanchy last year on the basis of tissue-thin allegations of racist phrasings in her award-winning book “Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me”.

Clanchy, an English teacher as well as an author, was for many years a passionate and effective supporter and tutor of immigrant children, in particular refugees, some of whom she had coached to spectacular success as creative writers. And yet after a couple of Twitter trolls took exception to her simple pen portraits of a few of the children—referring to skin colour, eye shape and the like in ordinary, non-pejorative language—she was called a Nazi, fascist, racist and the like. Her publisher dropped her; she has written since about how she was driven close to suicide, in particular by snide and vicious remarks by Joanne Harris, chair of the Society of Authors.

The most striking thing about these types of allegations, after how concocted they are, is that they are highly contagious. The way it works is this. Someone you know or have made approving remarks about is accused of racism for something minor or non-existent. You’re now in a difficult and dangerous position. Do you denounce them, if necessary apologising for ever having anything to do with them, in the hope of saving yourself from contamination? Or do you stand by them and say that you don’t see what is racist about whatever they’re being accused of—in which case you’re not just racist too, but mired in privilege as well?

This dynamic of spiralling denunciation plays out with other false accusations of “bigotry”, too. The published disclosures in Maya Forstater’s employment-tribunal case, and her witness statement, clearly show that when colleagues at the Washington headquarters of the Center for Global Development (CGD) raised concerns about her supposedly “transphobic” tweets, her colleagues in London were baffled. Some replied saying they couldn’t see anything wrong with what Maya had said—at which point it was made plain to them that if they couldn’t see the transphobia, they must be transphobic too. It’s worse than the fable of the emperor’s new clothes, in which embarrassment and the fear of looking stupid drove the courtiers to tell the emperor he looked wonderful in his diaphanous robes. When the other person is supposedly racist or transphobic, admitting you can’t see it means you’re not merely stupid or unsophisticated, but just as bad as them.

And so you see the racism or transphobia. You see it good and hard, if necessary rewriting history to give it substance. Maya’s first judgment, which concluded that her beliefs were not worthy of respect in a democratic society, relied heavily on her accidental misgendering in a tweet of a non-binary identifying man some months after she had left CGD—which, to state the obvious, cannot possibly have been anything to do with why she lost her job.

By the time of her third hearing, nearly 100 of her ex-colleagues worldwide had signed a letter to the think-tank’s senior management, urging it to continue fighting her ultimately successful claim against it. The letter represents her as a serious danger to trans people, and CGD’s discrimination against her as bravely standing up for social justice. It’s still common to see people online and in the media claim that she harassed a trans colleague (there was never even the slightest hint or accusation that she had harassed anyone, and she had no trans colleagues).

And once people are lying to themselves and others about what actually happened, and what they used to think, the person it’s all about becomes their enemy. That person is the cause of their cognitive dissonance, after all. As long as Maya remained in the London offices of CGD, her colleagues there would continue to suffer attacks from their Washington colleagues, and potential future harms to their careers in a globalised, Americanised jobs market. But they also knew she had done nothing wrong and was being treated terribly. To me, it looks like they wanted her gone not just for the sake of a quiet life and to protect their future earnings, but because she was a standing reproach to their own cowardice.

They weren’t wrong to be afraid, however. These bigotry bombs can be incredibly powerful, taking out even relatively distant bystanders if they aren’t disarmed.

The explosive force of the Clanchy affair seriously wounded Philip Pullman, the Society of Author’s president, who defended her from the accusations of racism only for the society to tell him publicly that he should attend race-awareness training. Shortly afterwards, he resigned his post.

The next victim was Philip Gwyn-Jones, Clanchy’s publisher at Picador. He also started off by defending her, saying to the Telegraph: “This idea that people can only write about certain types of individuals because they happen to be proximate to these individuals—that is a death knell to literature and literature of the imagination.” After he was accused of being racist himself, he made a grovelling apology: “I now understand I must use my privileged position as a white middle-class gatekeeper with more awareness.” But that was too little too late. Shortly afterwards Picador let it be known that Gwyn-Jones was stepping down “to pursue other opportunities”.

I cannot stress this strongly enough: Kate Clanchy did nothing “racist”. Far from it, she was a committed and staunch antiracist campaigner. The immigrant pupils she taught, some of them refugees, adored her for helping them find their voice and for championing them. “I do have ‘almond-shaped eyes’. My teacher Kate Clanchy described me beautifully,” wrote Shukria Rezaei, one of those pupils, in the Times. But even this public show of support couldn’t contain the force of the blast. Clanchy had become, as she says Joanne Harris told her, a scapegoat for the entire publishing industry.

I think accusations of bigotry are often scapegoating: picking a single victim with the intention of allowing everyone else to avoid punishment. And sometimes I think they can be what I’m tentatively calling “figleafing”—trying to find some shred of commonality with people whose approval you seek, in the (usually vain) hope that this will convince them not to denounce you. The figleaf may be a single policy of theirs that you agree with, an individual that you both approve of—or a common enemy. The crucial point is that it gives the potential outcast the feeling that their apostasy can be concealed.

I think this explains the way even some rather good journalists cling to the idea that “some children” benefit from social transition and puberty-blockers, even as their own reporting shows that there is no evidence of benefit and plenty of evidence of harm. It could also explain why some people who accept in general that people can’t change sex hold onto the idea that very occasional people are “really trans”. Both are a way of trying to appease those on the other side by distancing yourself from supposed “real bigots” on your own by saying: look, you and I agree across enemy lines on something.

A third example of this came during Donald Trump’s presidency, when many of those opposed to trans ideology fulminated about the wickedness of his administration’s policy on transgender people in the military. That policy was perfectly sensible—it didn’t actually bar trans people from the military, as was widely claimed, but merely required that they satisfied the fitness standards for their own sex and barred them from the other sex’s communal accommodation. These are exactly the principles that any sex-realist would want to see upheld everywhere—and yet you would think Trump had demanded that all trans-identified soldiers be court-martialled. He was such a reliable bogeyman, and it was so unpleasant to think of agreeing with him on anything, that I’m sure people seized gratefully on any chance to distance themselves from “transphobia”.

I don’t think I truly understood until the past two weeks how painful committed left-wingers find it to be associated with people from different parts of the political spectrum. I’ve never experienced that personally, because I’ve never been left-wing, not even as a student. I’ve always felt detached from party politics. This fight has made strange bedfellows, which is much less discombobulating for right-wing people, because their politics are more pragmatic.

And also because they’re less prone to the delightfully self-aggrandising assumption that merely by being on their side of politics, they are thereby Good People, and that this moral superiority will be recognised by everyone. I think this brings into play a mental quirk called “moral licensing”, whereby someone who does something they think is good becomes more likely to grant themselves permission to do something that emphatically isn’t. I think people on the left live in a permanent state of moral licensing: they’re on the left, therefore they’re good, therefore any nasty thing they do can be excused.

That includes being associated with their own very nasty people. I don’t know how leftwingers can seriously argue that their own lunatic fringe, one which is moreover mostly inside Labour rather than outside mainstream parties, is any better than the right-wing extremists they regard as such toxic pollutants that even the most tenuous connection must be denounced publicly.

I got a lot of nice DMs, texts and emails in the past two weeks, and some heartfelt and reasonable messages from people who thought I had messed up by going to Brighton. But I also got a couple of really nasty messages from people I know and thought I respected. The self-righteous, entitled tone was startling—until I remembered that the senders think they belong to the Righteous, and therefore give themselves permission to talk in a way that they would otherwise recognise as unacceptable.

One of those messages said that I was “disingenuous” in last week’s article—its writer claimed to be able to tell that I knew I was equivocating about racism, and didn’t believe what I wrote. That word, disingenuous, has been used a lot on social media too, not just of me but of other people who have dared suggest that no, Posie Parker is not a “pound-shop Marine le Pen” who cares about nothing and nobody but herself, as one widely noticed and now-deleted tweet had it.

I think at least part of the reason for that accusation of disingenuousness is that people can’t believe that they ever liked, or respected, or even tolerated someone who would refuse to join in the latest denunciation. So I must only ever have been pretending to be decent and respectable, and they now feel betrayed. And of course it has to be my fault. It can’t possibly be that they misunderstood my position all along; I must have been deceiving them.

So if I don’t think Hearts of Oak’s presence at the rally in Brighton makes Posie Parker is a racist, how do I explain that presence? Simple: the far right will always turn up on one side of a police line if the far left is on the other. (The same is true in reverse, obviously.) Hearts of Oak were on the Let Women Speak side of the police line because the Queer Anarchists—men dressed in black, with balaclavas and knuckledusters—were on the transactivist side. The same sort of people turn up to protests against Drag Queen Story Hour outside schools and libraries, and for the same reason: the far left is inside, in the form of men dressed as parodies of womanhood who think that this makes them especially suitable to read to children.

Perhaps the most revealing thing that was said during the past fortnight was that this far-right presence at the Brighton rally would be “unhelpful” when it came to fixing the gender-activism problem “within the left”. For me, this was like a lightbulb going off: the people saying this understand that gender-identity ideology was birthed on their side of politics, and they want to strangle it there too.

I’ve often heard left-wing friends say that gender ideology isn’t, in fact, left-wing. And I know what they mean: it shouldn’t be. There’s nothing inherently egalitarian or supportive of the poor and oppressed in lying about material reality, indoctrinating and sterilising kids or endangering women. But as a matter of historical fact, it arose in what someone I know calls the “gentry left”—that part of the left that lives in university campuses, political-party ranks, trade unions and everywhere that graduates run the show.

Perhaps the gentry left wants to throttle gender lunacy behind closed doors because it’s so embarrassing to be its origin. Or perhaps it’s because the only end to genderism they are willing to contemplate is as part of a glorious socialist future. Have a read of the Woman’s Place UK manifesto. The group started as a single-issue campaign against gender self-ID, which everyone except the genderist left could rally around. Its broader platform, however, is to bring about a gender-free Marxist utopia—a goal that hardly anyone in Britain shares, and which will happen, if at all, only in some far-distant future.

This isn’t my vision of the way I want the world to be, and I’m not in this fight to help rescue the left from its lunatic fringe. I’m in it, and always have been, in part to protect women’s existing sex-based rights but mostly to try to limit the number of children indoctrinated and sterilised by the world’s nastiest neo-religion.

And the idea that the best way to do that is to wait until the GC left throttles the genderist left is, frankly, absurd. It will be far quicker to go around them than to try to bring them round. Outside the left almost everyone understands, once they know what’s going on, that gender-identity ideology is idiotic and dangerous. So do an increasing number of Tory MPs and ministers.

In a democracy the quickest way to change policies is to influence the administration, legislature and voters. Right now that’s best done by talking to the centre and mainstream right, and leaving left-wingers to fight among themselves.

If you were forwarded this edition of Joyce Activated and would like to subscribe, click below.