Joyce activated, issue 78

In this issue I share an extended version of my speaking notes for an event with Richard Dawkins, organised by Conservatives for Women, at the House of Lords on March 12th.

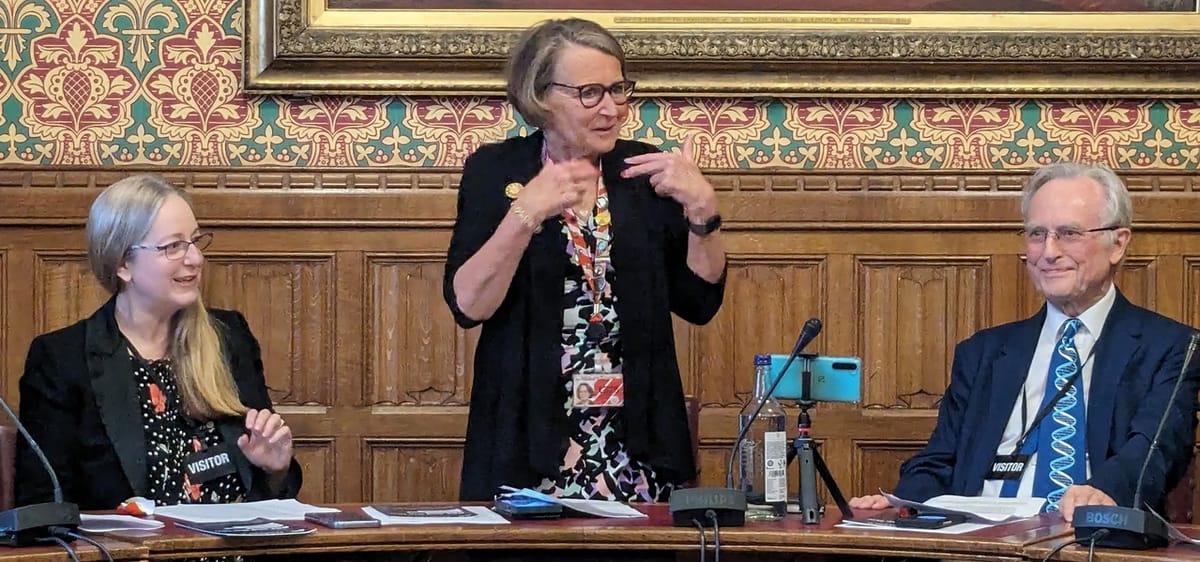

In this issue, I’m sharing an extended version of my speaking notes for an event on March 12th in the House of Lords at which I spoke along with Richard Dawkins. The event was chaired by Baroness Anne Jenkin and organised by Conservatives for Women, an incredibly energetic and effective group within the Conservative Party. The title was “Why there are two sexes, how we know and why that matters”, and it was open to all MPs and peers, as well as to their staff by prior arrangement.

Dawkins spoke first, taking about 15 minutes to explain what a “sex” is, how we know there are two and only two, how sex differentiation works and how the sex of an individual is determined. I’d say that it was a dream come true to be co-platformed with him, except I don’t think I could ever have dreamt that something like that might happen.

I’m a huge fan of Dawkins; “The Selfish Gene” is among a handful of books that have had the most profound influence on me. The first agent to take an interest in my work – she dropped me when she read my details book proposal; it turns out that when she expressed willingness to be “courageous” she hadn’t really meant it – asked me what book I would most aspire to emulate, that’s the book I cited. Once my book was eventually written, and I heard from my editor that Dawkins was willing to provide an endorsement, I can’t express how delighted I was.

I knew she had sent the manuscript to him, and I was pretty sure he was reading it when I saw him a few days later tweeting about Rachel Dolezal, asking what the difference was between her identifying as black and a man identifying as a woman – a question I had made much of in my book. The following day – a Sunday – my editor messaged me to say: look at your email. The only endorsement that could possibly have meant more to me would have been one from JK Rowling, the queen herself.

In 2015, Rachel Dolezal, a white chapter president of NAACP, was vilified for identifying as Black. Some men choose to identify as women, and some women choose to identify as men. You will be vilified if you deny that they literally are what they identify as.

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) April 10, 2021

Discuss.

In brief, he distinguished between three related concepts: sexes as categories – which follows solely from whether the organism, or part of an organism, evolved to support the production of large gametes (female) or small gametes (male); sex differentiation – the developmental process whereby an organism develops along a sexed pathway; and sex determination (working out which sex a particular organism is – in humans largely done by looking a baby’s genitals in utero via ultrasound, and then again at birth – only if there is an anomaly is anything more complicated required).

The questions he was asked were fascinating too (the event was held under the Chatham House rule, meaning I can’t identify who said what). One attendee perceptively said that trans ideology was a highly successful example of a meme – a concept invented by Dawkins, meaning an element of a culture or system of behaviour passed on by imitation or other non-genetic means, and which is, like genetic traits, subject to a type of evolution. Another recalled reading about James/ Jan Morris’s “sex change” when he was at boarding school: it had been a topic of conversation among the boys, he said, and they took it as surprising but factual that doctors could indeed “change one’s sex”.

A third said to me afterwards that though she is severely disturbed by the harms caused by transgender ideology, especially to children, she had always been “terrible at biology” and hadn’t known any of that stuff about DNA and chromosomes, so it had been useful to hear Dawkins explain what sexes are.

When it was my turn to speak, I focused on the “why it matters” part of the title. These are my speaking notes, hence the numbering and bolded sections. I’ve added reflections inspired by attendees’ questions and responses [in square brackets].

1. Most people do know that there are two and only two sexes, and that sex can’t really change. [I’m still sure this is true, despite the comments about Jan Morris and being bad about biology. To adapt something Kellie-Jay Keen once said, most people aren’t vets, but they still know what a dog is.]

2. But they are confused about the idea of sex, all the same, because “changing gender” or “sex change surgery” or ‘transitioning’ have been discussed so much they think these must really mean something, even though they wouldn’t be able to explain what that something is. They may think there are people who were “born in the wrong body”, or have “fully transitioned” or “had the operation”. They have the idea that a man has to undergo a great deal to “become a woman”. They think sex does not equal gender, or that it’s possible to have a brain of the “opposite sex to your body”. They think doctors know how to tell who is trans. [The questions suggested that at least some people are a bit more uncertain than I had realised. The main point, though, is that when it comes to the idea that there’s such a thing as being trans, people really aren’t thinking deeply or coherently, or indeed at all.]

3. Having said that most people accept there are two sexes, many have fallen victim to a Gish Gallop, named for Duane Gish, an American young-earth creationist who died a decade ago, who would fire out unrelated falsehoods, half-truths, irrelevancies and misrepresentations to overwhelm his debating opponent. Here are four elements of a Gish Gallop on the meaning of sex that I’ve often seen. [These are adapted from my book.]

i. The notion of binary sex is an artefact of Western colonialism. Before white people arrived, indigenous peoples were too wise to think that humans came in just two physical types. The fa’afafine of Samoa, the muxes of Oaxaca, India’s hijra and the ‘two-spirit’ people of some Native American tribal groups are cited. Never mind the racism inherent in claiming that the rest of the world needed Europeans to explain how reproduction worked; such third genders have no bearing at all on these traditional societies’ understandings of biological sex: they’re about incorporating non-conformity, most often male homosexuality, into patriarchal societies.

ii. ‘Nemo’s Law’: if you mention sexual dimorphism, someone will bring up clownfish, which are “sequential hermaphrodites” born with the potential to mature into either males or females. That person will then imply that since clownfish can change sex – or, more generally, that since not all living things are sexually dimorphic and incapable of changing sex – there is no objective distinction between male and female. But you need a definition of male and female to observe that clownfish can change sex – or that some other living things are hermaphrodites, or reproduce asexually – and then you can see that sex in humans is binary and immutable. [In fact, Dawkins had already given this example, but I like the Nemo’s Law quip so much I gave it again.]

iii. People with intersex conditions prove that sex is not binary. In her 1993 essay, “The five sexes”, Anne Fausto-Sterling, professor of biology and gender studies at Brown University, argued that five sexes should be recognised: male, female, merm, ferm and herm (the extra ones are: males with some female aspects, females with some male aspects and people who possess one testicle and one ovary). Then she goes further, describing sex as a ‘vast, infinitely malleable continuum that defies the constraints of even five categories’. She gives startling estimates for the prevalence of intersex conditions: 4 percent in the essay; 1.7 percent in Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality, a book published in 2000.

Such figures are nonsense. To get to even 1.7 percent you must include people with developmental anomalies that are so minor they may never become apparent, as well as more serious conditions that still create no difficulty in classifying a person as male or female. The share of people whose chromosomes do not match their body type (the XY karyotype that normally builds a male body together with breasts and a vagina, for example), or whose physiology is so ambiguous that medical investigation is required to class them as male or female, is more than a hundred times lower.

More importantly, the argument is nonsense. “Sexes” are classes defined by the developmental pathways that evolved to produce gametes: eggs and sperm. As with any part of the body, reproductive organs may develop in anomalous ways, just as some people are born with extra fingers or toes, or missing eyes or legs, but humans are still ten-fingered and ten-toed, binocular and bipedal. For there to be even three sexes there would have to be a third gamete, and there is not. [Dawkins had referred to Fausto Sterling’s essay as well, so I squeezed this down. I did take the opportunity, however, to direct people to an FAQ on DSDs on the Sex Matters website.]

iv. Sex – not gender – is socially constructed. This is a claim of breath-taking proportions, given everything that is known about the mechanisms of reproduction and humanity’s shared evolutionary history with other sexually dimorphic species.

It is most closely associated with Judith Butler, who claims that sex and gender are not distinct things, and that sex/gender is socially constructed.

Most people think that “trans” means something like: you were born male and become female (and they’re very sketchy on the details and either don’t really think it happens or don’t know how it does, or think that the second bit refers to “gender”, not “sex”). But anyway, they do think you’re born one sex or the other. What Butler is saying is that you aren’t. You’re “assigned male/female at birth”.

She claims that what medical professionals do when they register a newborn’s sex is not observational, but ‘performative’. A performative utterance is one that changes social reality. Marriage vows, which turn two single people into a legal couple, are an example. In Butler’s vision, medical professionals make children male or female by classifying them, and children are shaped into boys or girls, and later men or women, as they adopt the gender performance associated with their assigned sex/gender. Being trans is what happens when a person’s emerging understanding of themselves conflicts with the assignation made by the doctor or midwife.

This isn’t mere ivory-tower nonsense: it’s repeated by all sorts of organisations that really should know better.

In an editorial in 2018, Nature argued for laws to privilege gender identity over what it referred to as “sex assigned at birth”, citing intersex conditions as “proof” that sex is a fuzzy concept. In an article in 2017 entitled “Beyond XX and XY”, Scientific American claimed that “the more we learn about sex and gender, the more these attributes appear to exist on a spectrum”.

The cover story of the latest New York Magazine is by Andrea Long Chu, who has written elsewhere that it was watching sissy porn that made him trans, has undergone genital surgery even though he said he didn’t think it would make him happy. He has written a book called “Females: A Concern”, in which he says that the “barest essentials” of “femaleness” are “an open mouth, an expectant asshole, blank, blank eyes.” [I bowdlerised this quote in the House of Lords, and said the original had been in unparliamentary language.]

In the latest article he argues that trans kids should “have the right to change their biological sex”. That you shouldn’t need gender dysphoria to get any gender-related interventions you want, there should be no age limits, it should be free and on demand, because it’s a human right to change sex. He talks about changing sex as something people do all the time, for example menopausal women taking HRT. This is the cover story of a major magazine with normally very high editorial standards – I wrote for it once and the editing process was rigorous.

4. It’s been made very difficult to talk about the two sexes. People have observed that you can get into trouble, or at least that in some unspecified way it’s rude, or bigoted, or hurtful. I don’t think it’s too strong to say there’s a taboo on it.

An analogy that comes to mind is that when I was a child, it was regarded as very rude to refer to a woman as “she” in her presence. If I ever did such a thing, I would immediately hear “Who’s she? The cat’s mother?” I’m still uncomfortable referring to a woman as “she” in her presence, and find myself wanting to use her name or some circumlocution such as “this lady” instead.

[Many of the attendees at the event nodded along with this. I have just looked up the origins of this rule, and most of the explanations are clearly wrong because they talk only of the rudeness of using third-person pronouns for a person in that person’s presence, whereas it’s definitely an injunction against using them for women specifically. This article speculates that the reason is that a female cat is a “she-cat” whereas a male cat is a “tom”, so “she” suggests that a person is an animal whereas “he” doesn’t – I have no idea if that’s right.]

Where does the general public stand on all of this? What follows comes from a variety of polling and focus groups, and from many, many conversations with campaigners and a wide variety of people who aren’t embroiled in the gender wars – on either side.

Overall the general public is accepting of the principle of people changing their gender identity. This is a summary of where the average person stands, to the extent that they give it any thought:

- It’s an individual’s choice to “change gender” and if someone feels so strongly about it, that should be a choice that person is free to make.

- They don’t want to be unkind or bigoted.

- Other people “changing gender” doesn’t affect them in any way.

- “Changing gender” has been very prevalent in media and cultural discourse, so it must be something generally accepted.

- And finally, an increasing number of people have a relative, friend or colleague who identifies as trans, which leads to a personal sense of loyalty or unwillingness to say anything against the idea of “changing gender”.

The great majority of people feel uncomfortable with anything they perceive as an attack on trans people. They think these unfortunate people are vulnerable, and that if accommodating them involves a bit of pretence, what does it matter?

They think that saying transgender women are men is harsh, unnecessarily confrontational and rude. The vast majority of people are happy to use a trans person’s new name and pronouns. To do so in social situations is being polite and in the workplace it’s seen as being professional.

A big part of this is workplace training. People have to do an awful lot of damn-fool training in the workplace. So if HR say “such-and-such was assigned male at birth but their gender identity is female”, or “Joseph is transitioning, you must now refer to Joseph as Josephine, she/her”, they just think “OK, this is the next thing I’m expected to do, times change, social norms change, a lot of things that once seemed impossible have come to pass, a lot of stuff I used to think was obvious is now overturned.” They aren’t engaging in any deep way; it’s simply “above their pay grade”.

5. Although people are accepting of the principle of changing gender – they don’t know what that means but don’t much care – they aren’t happy with specifics beyond name and pronouns and not being horrible to people who are visibly trans. In particular, they are not happy about the participation of “trans women” in women’s sport, or about children doing anything they perceive as serious or irreversible.

Some people – let’s call them trans-sceptic – are already aware of at least some specifics they’re unhappy about. Others – let’s call them trans-positive – are more sure of the principle that “trans women are women” and “gender is self-identified”. But the first group isn’t willing to be what they regard as “rude”; and the second group is unwilling to follow their principles all the way to their logical conclusion – even if they’re quite vociferous about those principles. In particular, even they don’t defend major medical interventions for children, or allowing the people they might call “assigned male at birth” to compete in women’s sports.

Sport is largely uncontested because it isn’t about whether trans women are women, it’s about sexed bodies, which people accept do not change no matter the sincerity or commitment of the “trans women”. They don’t have to express an opinion on something controversial (at least they don’t think they do) and they don’t have to enter into an argument they know is highly charged about the meaning of words. They can say something very short and simple that doesn’t make them feel like they’re being mean or bigoted – that in fact makes them feel like good people – namely, “it’s not fair”.

Similarly, when it comes to children, there’s something very obvious and easy to say that comes readily to mind, doesn’t trigger the protective impulse to avoid a charged, dangerous topic, doesn’t require a general statement about other people’s identities and makes them feel like good people rather than bad ones: “they’re too young”. Good parents – indeed good adults generally – protect kids from the consequences of their own naivete and ignorance.

6. Appealing to the mainstream therefore means moving the debate past general principles and onto specifics. Keeping the discussion on safety, privacy, fairness and dignity for women – rather than bringing the argument back to the principle that transwomen are men.

The difficulty is that when it comes to single-sex spaces and services, people are absolutely desperate to sidestep any consideration that might require saying No – especially if they might have to be the one to do so. They think “someone else” should sort it – and if you push them, they say that it should be the government.

[I didn’t have time to go into this in detail in the House of Lords, but I’m always very sceptical when people say “government” should sort something out. This doesn’t mean they would actually vote for someone who presented a worked-out policy on the issue that made clear who were the winners and losers; it merely means that they aren’t willing to work out the winners and losers themselves, or to accept any losses themselves, or to tell anyone else that they must lose out. They just mean “I accept that it’s a problem, but it’s not my problem”. And politicians know this perfectly well. They know that there are no votes in adjudicating on hotly contested issues: the people who win are rarely grateful while those who lose can howl very loud.]

To take just one example of the way people will equivocate rather than simply say “sorry, single-sex spaces matter too much to allow people of the opposite sex in, no matter how much they want to come in”, consider public toilets. Even people who say that the trans stuff is all nonsense will say either that toilets don’t matter because the cubicles have doors, or that the best solution is to make all public facilities single-user and “gender neutral”. They don’t think through any of the many other reasons we have single-sex toilets, from privacy and safety to hygiene, cost and efficient use of space. And they don’t think how this switch is much harder on women than on men.

[As an aside, why doesn’t anyone suggesting that all the men attending sporting events or going out to pubs use lavatories rather than urinals ever spare a thought for the cleaners? Whenever I hear someone say “your toilet at home is gender-neutral”, I not only think “yes, but strangers aren’t allowed to just walk in off the street and use my toilet” – I also think “yes, but don’t you know that little boys have to be taught not to wee on the seat and the floor, and judging by the state of the loos on trains, lots of adult men have never learned?”]

To take another example, which really surprised me at first: people are surprisingly willing to accept gender self-ID on nominally single-sex hospital wards and in prisons. The reason seems to be that there are managed spaces so people – again desperate to avoid the idea of having to ever say “no” – argue that we can trust the authorities to make the policy work. Again, they don’t think about privacy, comfort or risk reduction. They don’t think how much easier it is for a woman to let her guard down when she knows that no men are present, supervised or not. If you bring up prisons, you’ll often be told that male prison guards are a bigger problem – and I agree that female prisons should be exclusively female-staffed. But the existence of one bad thing doesn’t mean we should simply accept another bad thing. And people know that perfectly well in other circumstances.

7. What you realise when you’ve heard enough people talk about a variety of single-sex spaces and services is that a lot of people don’t know the reasons why these matter, or at least aren’t willing to admit that they do. And this is where we turn back to what Richard had to say about what the sexes are – the places that are still sex-separated, and the accommodations in law for sex, are where sex matters. Because sex is baked through us, it’s not just genitals – that’s the fallacy that’s known as bikini medicine. Every part of a female human is female; and every part of a male human is male.

All the situations where it’s best, for one reason or another, to provide a space or service to just one sex, or to the two sexes separately, come back at their root to some difference between the sexes. Think of toilets: the reason it’s best to have urinals for men in places like pubs and sporting venues is a simple matter of physiology. And the reason for building in several layers of privacy for women’s toilets is also in part related to physiology: our plumbing requires us to undress from the waist down to pee, and it’s good to know that there are at least two doors – and strong social norms – between you and any man when you’re doing this. It’s also partly related to women’s greater vulnerability to sexual predation, and men’s greater propensity to be sexual predators. This too is evolutionary in origin.

You can go through all the places where we still distinguish between the sexes and point to evolved differences to justify each case. But the long history of fighting unwarranted restrictions on women has left many feminists deeply reluctant to make such arguments.

This is a big part of the reason it’s become so difficult to say that there are real and meaningful differences between the sexes that go beyond bikini medicine, and beyond socialisation. Many women are afraid, for good reason, that accepting the existence of real, wide-ranging differences between the sexes is tantamount to accepting everything feminists have fought so hard against, from marital rape and unpunished sexual and intimate-partner violence to women’s exclusion from political power, business and higher education.

And so, here we are, with the project to legally “abolish sex” remarkably far advanced. To pick one indication, the Economic and Social Research Council provided full funding for the “Future of Legal Gender Project”, a UK university project running from 2018 to 2022 which sought to demonstrate the feasibility of ending any legal registration of sex. The Yogyakarta Principles, a strange, transhuman declaration written by a self-selected coterie of human-rights lawyers, similarly calls for an end to the registration of sex at birth – but simultaneously, and incoherently, for the right to register one’s gender identity in its place, and to have that gender identity registered on the birth certificate of any baby to which you are a parent.

The thing is – sex really does exist. It existed before there was language, before there were humans. And the reality of who has power and money, who’s stronger and who’s more vulnerable, who’s the default and who’s the exception, mean that it’s women who will suffer most if we pretend otherwise. To take just one example, it’s women who wipe the toilet seat before using it when a man has pissed on it – and it’s women who will no longer be able to use the ladies’ as a place to hide when a man is making a nuisance of himself in a bar. It’s men who will take advantage of gender-neutral toilets to follow a woman into a less overlooked area and choose the right moment to push her into a small, enclosed space with a floor-to-ceiling lockable door.

So what I would plead for is that we focus on the “why it matters” bit of the title. When we’re arguing about what sex means we’re either playing on Gish Gallop territory, or we’re telling people what they do know, but really don’t want to say.

Yes, we do have to make it easier to say that there are two sexes without being sacked or ostracised.

And yes we do need to be able to talk about the sex of some specific people who seek to destroy other people’s rights by insisting on forcing others to go along with their claims about their sex (in single-sex spaces and sports, for example).

But most of all what we need to be able to talk about is why the sexes – the two categories – matter, for everyone (but in particular for women), but not as some abstract speech right but rather in specific, concrete circumstances.

After Richard and I took questions, Maya Forstater was invited to make some concluding remarks. Her first was that I had left out one of the reasons why people have started to believe, or at least say that they believe, that sex isn’t binary and immutable: that laws have been changed so that the legal categories no longer match the biological ones.

Lawyers are strange people. They tend to think that laws create reality, not just in the circumstances when they actually do – when someone lawfully recognised as having the power to carry out marriages pronounces a couple “husband and wife” they really do become husband and wife – but also in circumstances where words cannot have such power.

Take, for example, the most idiotic thing that may ever have been said in a UK court of law: an argument presented during one of the hearings on the “For Women Scotland” challenge to the Scottish government’s attempt to introduce quotas for women on public boards. The definition it is seeking to use would define “woman” as anyone in possession of a birth certificate or a gender-recognition certificate stating their sex as female – that is, as including some men. The barrister representing the Equality and Human Rights Commission told the court that the idea that “sex” and “legal sex” were separate concepts was fundamentally flawed because sex was whatever the law said it was. Think of the speed limit, he said: there isn’t a “speed limit” and a “legal speed limit”: the legal speed limit is the only speed limit there is.

This is the sort of thinking we’re trying to challenge when we ask someone like Richard Dawkins to talk about the meaning and binary nature of sex. That there are two sexes is a fact that predates the existence not just of laws but of language, and indeed of human beings, by more than a billion years. We can no more turn a male human being into a female human being by the operation of law than we can turn oxygen into nitrogen by renaming it, or alter the speed at which objects fall towards the Earth by declaring its mass to have to changed. I agree with Maya that this is something I should have included – and I invite readers to suggest other omissions.

The second thing Maya said was that we should do the event again, but this time in a larger venue with tickets on sale to the public. Richard said he would be keen. What do readers think?

In other news, I did an interview on fan fiction with Louse Perry for her podcast last week, and it’s been released. You can watch it here.

And lastly, I’d like to thank everyone who got in touch or left a comment after my previous issue. They were so insightful, and I hope to find time to reply soon. I’m feeling a lot better now and pretty much back up to speed, not least because of all the wonderful people who’ve told me to keep my chin up and keep going.