The trouble with workplace affinity groups

And what the newly founded SEENs (Sex Equality and Equity Networks) need to do differently

Last week Sex Matters brought together representatives from the various “SEENs” – Sex Equality and Equity Networks” – that have sprung up over the past year in a wide variety of workplaces and sectors. They started with the civil service, and some are still nascent – TUSeen, one for unions, only launched over the weekend, inspired by the meeting to go public. Their structure and operation vary depending on various factors, such as whether they relate to a specific workplace (a government department) or a sector (the arts), and on whether people in that sector have strong employment rights (police) or are largely freelancers (publishing). But all have the same ultimate aim: to advocate for workers with “sex-realist” beliefs and push back against the influence of LGBT affinity groups and captured women’s groups that push trans ideology to the detriment of others and society as a whole.

If you are not a subscriber to my weekly newsletter, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

To prepare for a session I chaired, I spent a while researching the origin and development of affinity groups. What follows is an expanded version of my notes that should be useful to anyone wondering what went wrong in workplaces over the past decade, and how we might start to fix it. It is pretty broad brush, since my aim wasn’t to give a history lesson, but to provide context that people could use to think strategically about what SEENs should do both now and in the future.

The first affinity groups were formed by black employees in American firms during the 1960s – the civil-rights era. Their aim was in part to advocate on a live societal issue, and in part to offer members mutual support and protection. In the 1970s and 1980s gay-rights affinity groups started to spring up in American tech firms and then more widely. These were initially about making connections with like-minded people and working together on external political actions – fundraising for floats in gay-rights parades, for example. In the 1990s these networks started to advocate within organisations too, in particular for the extension of partner benefits from opposite-sex to same-sex couples.

Now 90% of Fortune 500 companies have at least one such group, usually set up, run and funded by the employer itself. They are usually called Employee Resource Groups (in a distinction I haven’t seen in the UK, Americans distinguish sharply between “affinity groups”, which are mostly about socialising around shared interests, and ERGs, which are funded and run by HR and are explicitly seen as part of an organisation’s DEI efforts). I’m just going to call them all affinity groups in this article.

To give a flavour of the range of identities now regarded as suitable for an affinity group, Raytheon has nine, relating to:

Indigenous communities

Black employees across the African diaspora

Disabled employees and their allies

Asians and Pacific Islanders

Hispanic and Latino communities

GenX employees

The LGBTQ+ community

Armed services personnel, their families, and veterans

Women’s success and empowerment.

Quite apart from the groups they are supposed to represent, affinity groups vary widely in how they operate. At one extreme are grassroots efforts to advocate with employers for a socially contentious position, in concert with external activists in a broader movement. At the other are groups set up, financed and run by organisations for their own purposes. Most groups exist somewhere in between, identifying with both the organisation and some societal subgroup whose interests they hope to advance. Members use this dual identity to advocate for their interests without violating workplace norms in what has been described as “tempered radicalism”.

Why might an employer set up, let alone fund and run, an affinity group? Boosters say they are useful for recruitment (and it’s certainly been my experience that recent graduates expect their employer to have at the very least a group for women (or perhaps “minoritised genders”), black employees (or perhaps “minoritised peoples”) and “the LGBTQ+ community”. The existence of affinity groups is also useful in signalling a commitment to diversity to current employees and external constituencies such as government, regulators, business partners (who may have diversity targets that extend to their supply chains) and customers.

Those who recommend employers set up affinity groups also claim direct business benefits. They say that by increasing minorities’ visibility and helping them network and gain promotion, groups contribute to the bottom line. They also claim that groups can help members advocate for organisational change, and help employers gain diverse insights when making decisions.

All this somewhat begs the question, however, since it assumes the changes and insights are bound to be good ones. The most circular reasons to set up a formal affinity group I saw cited were in order to get funding for the group, and in order to get permission to hold group meetings during working hours.

I don’t deny that an affinity group may provide genuine benefits for both members and businesses. The world isn’t so perfect that historically oppressed groups never need mutual support and protection. But a lot of this is cheap virtue-signalling: doing something easy and superficial to look “inclusive”. All too often a company sets up a women’s group, or an LGBT group, or whatever, appoints a woman or gay/trans person to run it, gives it a bit of money, a room to meet in, access to the company intranet and thinks “job done”.

Needless to say, while I did find a few nods to a potential downside of formal affinity groups – namely that they might advance some employees’ interests while alienating or harming others – nowhere did I find this cynical viewpoint in the literature.

Nor did I find much recognition that they are inherently prone to conflicts of interest. One exception was this illuminating paper on their history and development, which described affinity groups as subject to the so-called “Iron Law of Oligarchy” – the tendency for organisations to drift from relatively open or egalitarian decision-making, whether formal democracy or grassroots self-organising, towards control by a self-appointed cabal. In this process, once-radical voices gradually become co-opted to speak for the status quo. This process may be more or less complete or extreme – this is the paper where I found that useful expression I used earlier, “tempered radicalism”.

As I read this, it reminded me of an expression I heard often during my stint in Brazil as a foreign correspondent: poder parallelo, or parallel power. This is how Brazilians describe the extra-legal, non-government rule of the drug gangs within favelas (informal settlements).

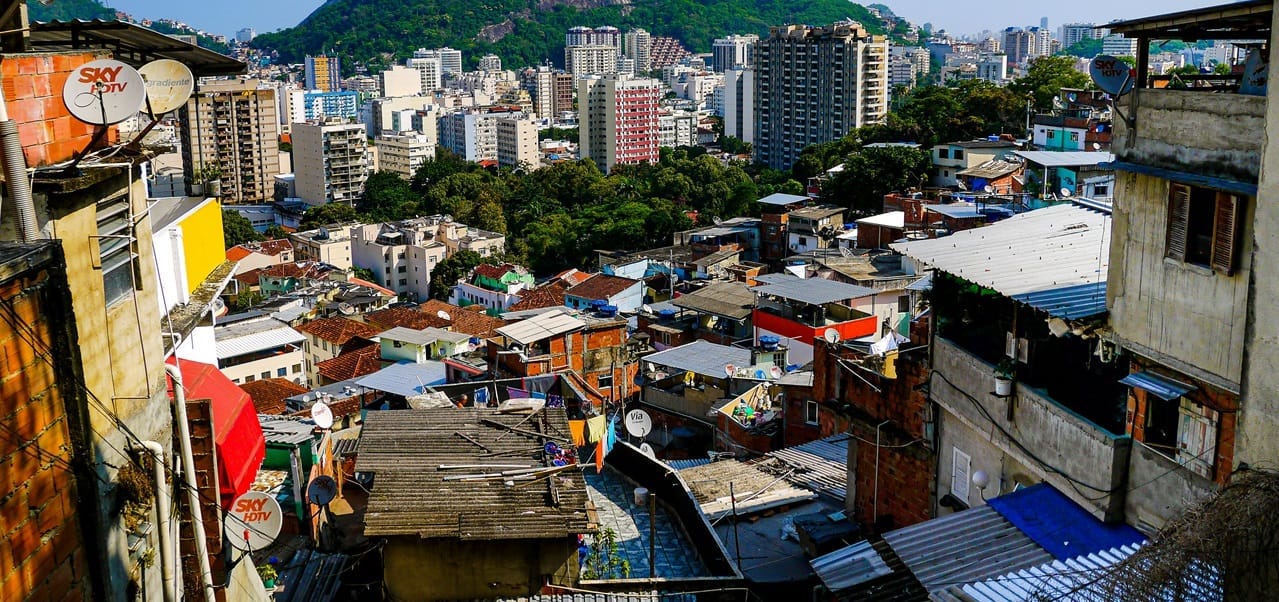

Some favelas are decades old, very large and pretty formal-looking: what’s lacking is formal land title and the institutions of the state (above is a picture from Rio, showing the juxtaposition of formal and informal that is so typical of that city). But they don’t exist in a state of lawlessness. In return for paying a sort of extralegal taxation, the gangs provide residents with the sorts of things people in formal settlements get from legitimate businesses and from the state itself.

These services commonly include minibus transport and illegal electricity and cable-TV hookups as well as events and entertainment (parties, Carnival floats). And they always include a rough kind of justice that may be resented but is usually regarded as better than pure anarchy, as the ruling gang acts not just to maintain its own monopoly on the supply of drugs but also keeps a kind of peace by settling property disputes and even administering beatings to punish crimes like rape and domestic violence.

Once a parallel power has filled the vacuum left by an incompetent or absent formal authority, it becomes very hard to dislodge. And sometimes, it seems to me, affinity groups come pretty close to being parallel powers within organisations. They constitute an alternate source of authority and chain of decision-making. Certainly in the case of the LGBTQ+ networks, they are backed up by a force outside the organisation that may be pursuing its own agenda and may have neither the interests of its supposed client community nor the host organisation at heart.

As an almost implausibly perfect case study in how affinity groups can go wrong, consider the LGBT+ group at Network Rail, the public body that owns and manages most of Britain’s railways. In January its head, Shane Andrews, posed with a mural of identity flags in London Bridge station, including the Progress Pride flag. After he responded to criticism on X by calling the women who complained “terfs” and “not worth my energy replying/ arguing/ debating”, some of the women he insulted trawled through his old tweets and found, let us say, a pattern.

Women, according to Andrews, are “bitches”, “sluts”, “slags” and “cows”; “miserable”, “stuck-up”, “dopey” and “ugly”. A while ago, I wrote about him and LGBT+ Network Rail in a column for the Critic. In it, I concluded that slagging off women functioned as a perverse kind of virtue-signal for Andrews and by extension Network Rail: it demonstrated allegiance to trans ideology, which, for a long time, won plaudits for both the company and Andrews himself. In 2021 Andrews was awarded an MBE for his work with the Scouts; Network Rail took the opportunity to boast that he had been “instrumental in helping us become more reflective of the communities we serve”.

Now that I know a bit more about the history of affinity groups, I think the problems at this particular affinity group go beyond this, and illustrate all three ways they can go wrong identified above.

As well as a vehicle for toxic virtue-signalling, the group is an example of the Iron Law of Oligarchy. Andrews is anything but suffering and downtrodden – such people don’t tend to get MBEs. And the group is a parallel power, not a genuine support group for sexual minorities within Network Rail but an arm of the gender-identity movement in wider society.

Andrews has stepped down from the affinity group. Network Rail has maintained strict silence on the subject, and did not reply to letters from women’s-rights campaigners about the flag mural in London Bridge, which is still there. I think it knows it has lost control of the group and that it is harming its reputation and operation, but doesn’t know what to do. Any attempt to rein it in or shut it down would surely be painted by the gender-identity lobby as a sign that Network Rail was now homophobic and transphobic – accusations it would struggle to deny, since it boasted that the network demonstrated that it was not these things. I’m sure it’s just hoping that somehow the problem will go away.

The new SEENs seem to me to be most like the early affinity groups for black Americans, in which a denigrated and discriminated-against group comes together to advocate with employers and for mutual support and protection. But good intentions clearly aren’t enough. What should they learn from history?

For now, I don’t have any answers, only questions. And the first is: what are they for? In the short term, are they aiming to gain the same benefits, voice and access to decision-making as the existing LGBT+ group and women’s group – or are they hoping to limit those groups’ influence? What’s their medium-term plan to avoid becoming a toxic virtue-signal, an oligarchy or a parallel power?

And finally, in the long term, what would success look like, and what’s the exit strategy? It would be awful to create a bunch of new Stonewalls, organisations that have achieved their policy goals but are too venal and self-serving to shut up shop and go home.

If you are signed up for free updates or were forwarded this edition of Joyce Activated, and you would like to subscribe, click below.